On Christmas Day, 1956, a baby was born in Germany with arms and legs that looked like flippers. No one knew why. That baby was the first of thousands. Over the next five years, more than 10,000 children around the world were born with severe, life-altering birth defects-all because their mothers took a drug meant to help with morning sickness. The drug was thalidomide, sold as a harmless sedative and anti-nausea medicine. Today, it’s still used, but under strict controls. And its story changed medicine forever.

How a "Safe" Drug Became a Disaster

Thalidomide was developed in West Germany in the 1950s. It was marketed as a miracle drug-non-addictive, gentle, and perfect for pregnant women suffering from nausea. By 1958, it was sold in 46 countries under dozens of brand names. In Australia, it was sold as Grünenthal’s Contergan. In the UK, it was Distillers’ Distaval. In Germany, it was everywhere. Doctors prescribed it freely. Pharmacies stocked it without hesitation. Pregnant women took it without a second thought.

But something was wrong. Babies were being born with missing limbs, deformed hands, paralyzed faces, and damaged eyes. Some had no ears. Others had internal organs that never formed properly. At first, doctors thought it was bad luck. Then, in 1961, two doctors independently made the connection. One was William McBride, an Australian obstetrician in Sydney. The other was Widukind Lenz, a German pediatrician. Both noticed the same pattern: every affected baby had a mother who took thalidomide during early pregnancy.

The window was terrifyingly small. The damage happened only between 34 and 49 days after the last menstrual period. That’s just four to seven weeks into pregnancy-often before a woman even knows she’s pregnant. One dose during that time could be enough. No amount of testing before pregnancy had caught this. No animal study had predicted it. The drug was approved because it worked for nausea and didn’t seem to cause immediate harm. But it wasn’t tested for what it did to developing embryos.

Why the U.S. Was Spared

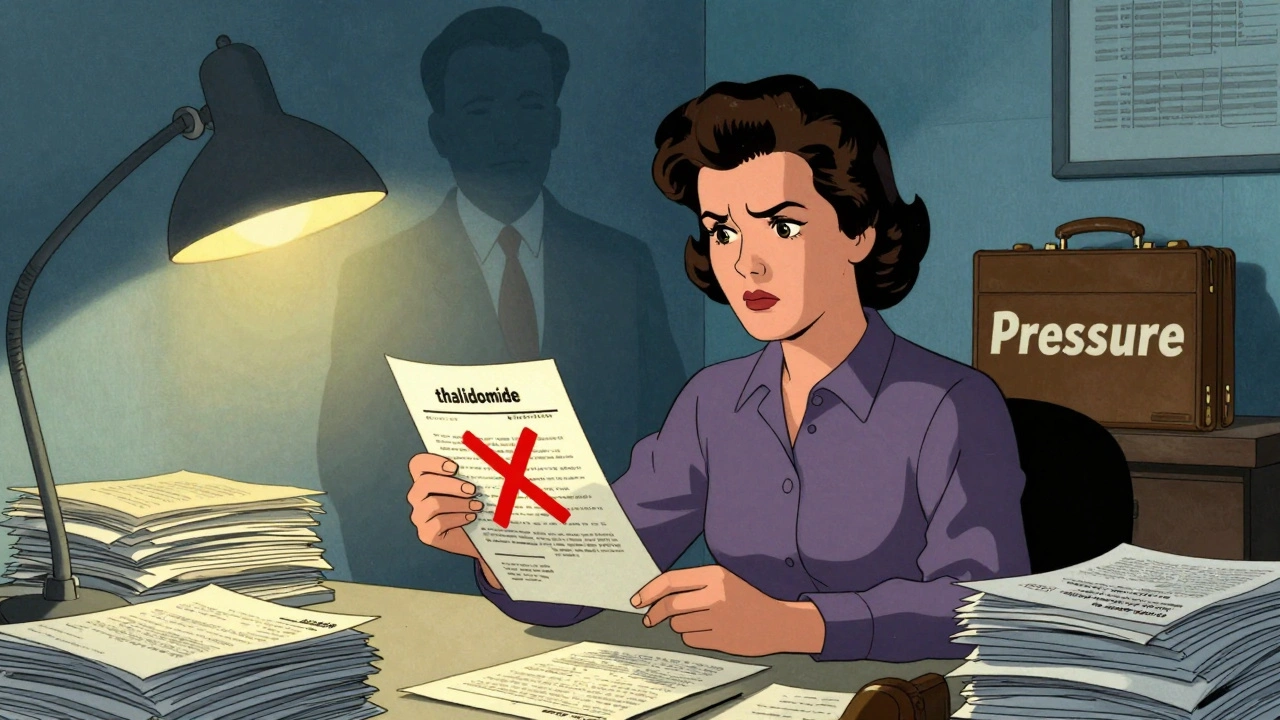

The U.S. didn’t have the same disaster. Not because American doctors were smarter. Not because American women were luckier. It was because one woman at the FDA refused to sign off.

Frances Oldham Kelsey was a medical officer reviewing thalidomide’s application in 1960. She saw gaps in the data. The safety studies were weak. There was no proof it was safe for pregnant women. She asked for more information. The drug company, Richardson-Merrell, pushed hard. They called. They wrote. They pressured. She held firm. Her skepticism saved thousands of American babies.

When the truth came out in late 1961, Kelsey became a national hero. She was awarded the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service in 1962. But her real legacy? She forced a change in how drugs are approved.

The Aftermath: Laws That Changed Medicine

The thalidomide tragedy didn’t just hurt families-it shattered trust in medicine. Governments had to act. In 1962, the U.S. passed the Kefauver-Harris Amendments. For the first time, drug companies had to prove two things before selling a medicine: that it worked, and that it was safe. No more relying on anecdotal reports or short-term studies. Clinical trials became mandatory. And for any drug that might be taken by women of childbearing age, teratogenicity testing became required.

Similar laws followed in the UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia. The UK created the Committee on the Safety of Medicines in 1963. Other countries built their own drug safety watchdogs. For the first time, regulators didn’t just trust companies-they demanded proof.

Before thalidomide, a drug could be on the market in months. Afterward, it took years. And that delay? It saved lives.

The Dark Side of a Miracle Drug

Thalidomide didn’t just cause birth defects. It also damaged nerves. By 1960, some long-term users-mostly older adults taking it for sleep-began reporting tingling in their hands and feet. Grünenthal added a warning to the label: “may cause numbness.” But no one connected that to the limb defects. It took decades to realize the same mechanism caused both.

In the 1980s, researchers discovered thalidomide blocked the growth of blood vessels. That’s why it worked against tumors-it starved them. But it also stopped blood vessels from forming in developing limbs. That’s why babies were born without arms or legs. In 2018, scientists finally found the exact target: a protein called cereblon. Thalidomide binds to it, and that binding shuts down the signals needed for limb development.

It’s a cruel irony. The same action that kills cancer cells also destroys growing limbs. That’s why thalidomide is still dangerous-but also still useful.

Thalidomide Today: A Controlled Lifesaver

Thalidomide didn’t disappear. It came back. In 1964, a doctor in Peru noticed it helped ease the painful skin sores of leprosy. That led to FDA approval for erythema nodosum leprosum in 1998. Then, in 2006, it was approved for multiple myeloma-a type of blood cancer. In clinical trials, patients on thalidomide lived longer. Their cancer progressed slower. Some survived three years longer than those on older treatments.

But here’s the catch: you can’t give it to a pregnant woman. Not even once. Not even if she says she’s sure she’s not pregnant.

Today, thalidomide is only available through the System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (STEPS). Doctors must be certified. Pharmacies must be registered. Patients must sign forms. Women of childbearing age must use two forms of birth control. They must take monthly pregnancy tests. Men must use condoms, because thalidomide can be in semen. Even the packaging has warnings in bold red letters.

It’s not perfect. Some patients still get pregnant. Some still get nerve damage. But it’s the best we have. And it works. Annual global sales are around $300 million-mostly for cancer patients who have no other options.

Lessons That Still Matter

Thalidomide isn’t just history. It’s a warning that never stops echoing.

First, drugs that seem safe for adults aren’t always safe for developing babies. That’s true for prescription pills, over-the-counter meds, and even herbal supplements. Just because something is “natural” doesn’t mean it’s safe in pregnancy.

Second, we still don’t test enough drugs for teratogenic effects. Many medications used in pregnancy have never been properly studied. We rely on animal data, which often doesn’t predict human outcomes. We rely on post-market reports, which come too late.

Third, trust isn’t enough. No doctor, no company, no regulator should be trusted without proof. The thalidomide tragedy happened because everyone assumed it was safe. That’s the danger of assumption.

And fourth-women’s voices matter. William McBride was dismissed by his university. Frances Kelsey was pressured by a powerful company. Both stood their ground. If we don’t listen to the people who see the patterns, more tragedies will happen.

What You Should Know Today

If you’re pregnant, or thinking about getting pregnant, here’s what you need to do:

- Never start or stop any medication without talking to your doctor.

- Don’t assume a drug is safe just because it’s sold over the counter.

- Ask: “Has this been tested for use in pregnancy?” If the answer is “no,” be cautious.

- Keep a list of everything you’re taking-prescription, supplements, vitamins, herbal remedies.

- Know that the first eight weeks of pregnancy are the most critical for development.

And if you’re a man taking thalidomide for cancer? Use condoms. Always. Even if your partner is on birth control. Because the risk isn’t zero.

Why This Still Matters in 2025

Today, new drugs are approved faster than ever. AI helps predict side effects. But we still don’t have perfect tools to test for birth defects before a drug hits the market. And we still have gaps. For example, many antidepressants, anti-seizure meds, and acne treatments carry known risks-but are still prescribed to women who might become pregnant.

Thalidomide taught us that the cost of speed is human lives. That’s why we still teach it in medical schools. That’s why the Science Museum in London has a permanent exhibit on it. That’s why every pharmacist who dispenses thalidomide must be trained.

It’s not just about one drug. It’s about how we protect the most vulnerable. The unborn child. The woman who trusts her doctor. The system that’s supposed to keep her safe.

Thalidomide was a failure of science, of regulation, of empathy. But it also became a turning point. It forced us to care more. To test more. To listen more.

That’s the lesson. Not fear. Not blame. But responsibility.

Can thalidomide cause birth defects even if taken before pregnancy?

No. Thalidomide only causes birth defects when taken during a very specific window-between 34 and 49 days after the last menstrual period. That’s when limbs and organs are forming. Taking it before conception or after the eighth week of pregnancy does not cause these specific defects. But it can still cause nerve damage in adults.

Are there other teratogenic drugs still in use today?

Yes. Several common medications carry known risks. For example, isotretinoin (Accutane) for acne can cause severe brain and heart defects. Valproic acid, used for epilepsy and bipolar disorder, increases the risk of autism and developmental delays. Warfarin, a blood thinner, can cause nose and limb deformities. Even some antidepressants and anti-seizure drugs have documented risks. Always check with your doctor before taking any medication during pregnancy.

Why wasn’t thalidomide tested on pregnant animals before being sold?

In the 1950s, testing drugs on pregnant animals wasn’t standard practice. Regulatory agencies didn’t require it. The assumption was that if a drug was safe for adult humans, it was safe for pregnant women. Scientists didn’t yet understand that fetal development works differently than adult physiology. Animal studies were done, but often on non-pregnant animals. Even when tests were done on pregnant animals, the results weren’t always interpreted correctly. The science of developmental toxicology simply didn’t exist yet.

Is thalidomide still prescribed today?

Yes-but only under strict controls. It’s approved for treating leprosy-related skin sores and multiple myeloma, a type of blood cancer. It’s not used for morning sickness or sleep. Every prescription requires enrollment in a safety program (STEPS), mandatory contraception, pregnancy testing, and signed consent. It’s one of the most tightly controlled drugs in the world.

How did thalidomide change how we test drugs today?

Before thalidomide, drug companies only had to prove a medicine was safe for short-term use in healthy adults. Afterward, they had to prove it worked and was safe for its intended use-including in pregnant women. New requirements were added: long-term studies, animal testing on pregnant animals, and specific tests for birth defects. The FDA and other agencies now require a pregnancy category or risk assessment for every drug. That system, born from tragedy, is what keeps most pregnant women safe today.

Jennifer Anderson

omg i just read this and i’m crying. i had no idea one drug could do that much damage. and frances kelsey?? queen. she literally saved lives just by saying ‘nope, not good enough.’

Sadie Nastor

this is one of those stories that makes you trust science less but regulators more?? like… how did we not know?? and why did it take so long to fix?? 🤔

Sangram Lavte

the fact that thalidomide is still used today for cancer but under such tight controls shows how far we’ve come. not perfect, but better than before. the STEPS program is actually a good model.

Oliver Damon

What’s fascinating here is the ontological shift in pharmacovigilance: pre-thalidomide, safety was assumed via proximal efficacy; post-thalidomide, it became epistemologically grounded in developmental toxicology. The regulatory apparatus didn’t just evolve-it was reconstituted. We now treat teratogenicity as a distinct pharmacodynamic domain, not an afterthought. That’s the real legacy.

Ryan Sullivan

So let me get this straight-some woman in the FDA stopped a drug because she was ‘skeptical’? Meanwhile, thousands of babies were born with flippers in Europe because everyone was too lazy to check. Classic American superiority complex. We didn’t save anyone-we just got lucky.

David Brooks

FRANCES KELSEY IS A GODDESS. I WANT A STATUE OF HER IN EVERY PHARMACY. THIS IS THE STORY WE SHOULD TEACH KIDS BEFORE THEY LEARN ABOUT THE CIVIL WAR.

Nicholas Heer

they say thalidomide was the cause… but what if it was the vaccines?? or the fluoride?? i read a forum where a guy said the real deformities came from the government’s secret radiation experiments on pregnant women. they covered it up with the thalidomide story. think about it. why do you think they rushed to make STEPS? to distract us.

Kyle Flores

my sister took an OTC sleep aid while pregnant and panicked for months. she called her doctor every week. that’s the kind of caution we need more of. not fear-but respect. we don’t know what every pill does to a fetus. so we ask. we check. we listen. that’s all.

Sam Mathew Cheriyan

wait so you’re telling me thalidomide is still sold? like… really? why not just ban it forever? someone’s gonna mess up. always is. i bet they’re still giving it to pregnant women in some back alley clinic. just saying.