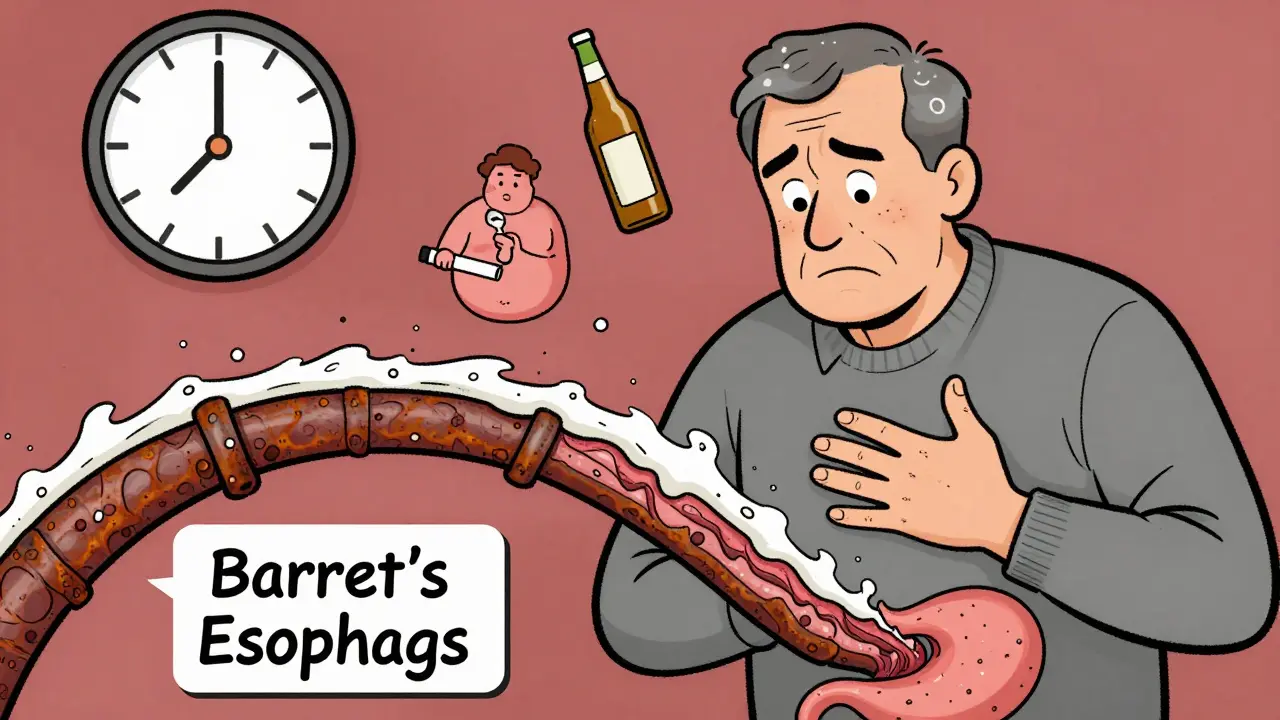

Chronic acid reflux isn’t just uncomfortable-it can be life-threatening. If you’ve had heartburn for five years or more, especially if you’re a man over 50, overweight, or a smoker, your risk of esophageal cancer is rising. Most people don’t realize that the same burning sensation they brush off as "just indigestion" is slowly changing the lining of their esophagus. What starts as irritation can become Barrett’s esophagus, a precancerous condition that, left unchecked, can turn into cancer. The good news? You don’t have to wait for symptoms to get worse. Knowing the real risks and red flags can save your life.

Why Chronic GERD Is the Biggest Risk Factor

GERD-gastroesophageal reflux disease-is common. About 1 in 5 Americans experience it regularly. But only a small fraction of those people ever develop esophageal cancer. Still, the link is undeniable. A 2023 study tracking over 100,000 people found that those with chronic GERD had more than three times the risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma compared to those without it. That’s not a small increase. That’s a major red flag.

The problem isn’t just the acid. It’s the duration. When stomach acid keeps splashing up into the esophagus for years, the body tries to adapt. The delicate lining of the esophagus isn’t built to handle acid. So, over time, it starts to change. Cells begin to look more like stomach cells. This is called Barrett’s esophagus. It’s not cancer. But it’s the only known pathway to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Think of it like rust on a pipe-slow, silent, and dangerous if ignored.

Not everyone with GERD gets Barrett’s. Only about 10-15% of people with long-term reflux develop it. But for those who do, the risk doesn’t stop there. About 0.2-0.5% of Barrett’s patients develop cancer each year. That sounds low, but when you consider how many people have GERD, the numbers add up fast. In the U.S., over 21,000 new cases of esophageal cancer are diagnosed every year-and most are caught too late.

Who’s Most at Risk? The Hidden Profile

If you’re wondering whether you’re in danger, look at the profile of someone who actually develops this cancer. It’s not random. The people most likely to be affected share a set of clear, measurable traits:

- Male: Men are 3 to 4 times more likely than women to get esophageal adenocarcinoma.

- Over 50: 90% of cases happen in people older than 55. New or worsening reflux after 50 is a major warning sign.

- White, non-Hispanic: White Americans have three times the rate of this cancer compared to Black Americans.

- Obese: A BMI of 30 or higher doubles or triples your risk. Fat around the abdomen pushes stomach contents upward.

- Smoker: Smoking increases risk by 2-3 times. And if you smoke and have GERD? Your risk multiplies.

- Family history: If a parent or sibling had esophageal cancer, your risk goes up.

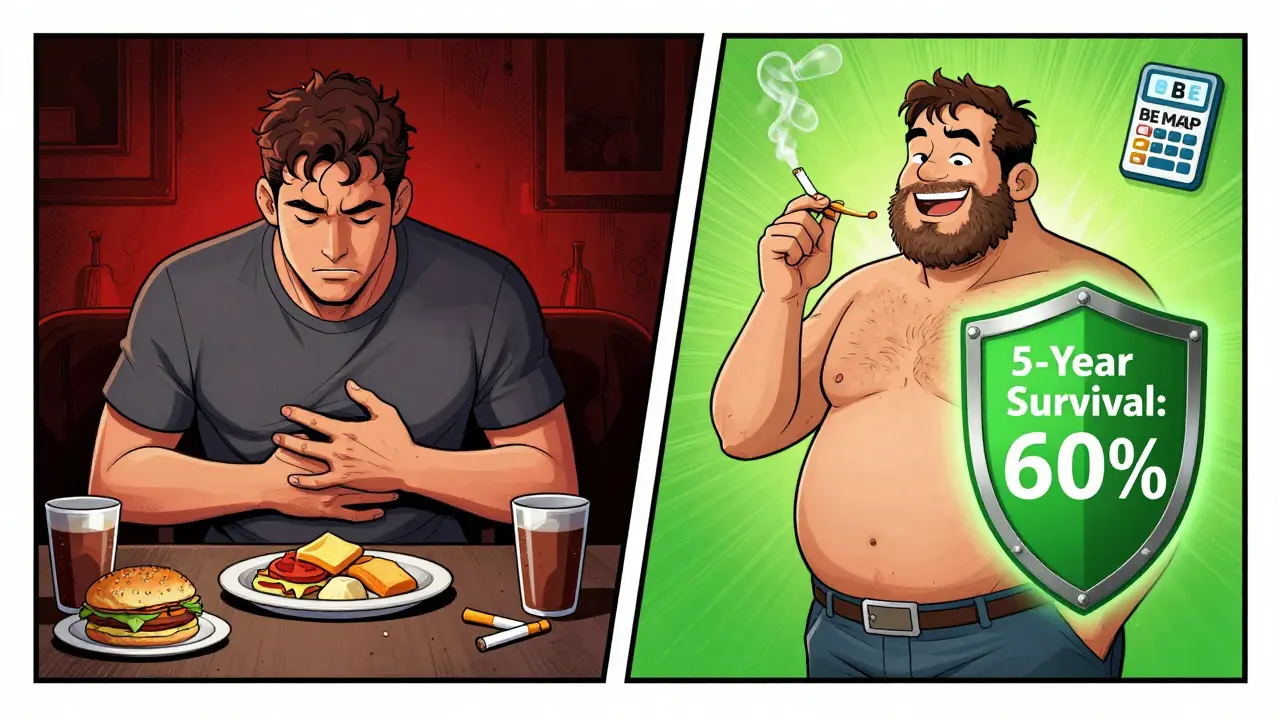

Having just one of these factors doesn’t mean you’ll get cancer. But if you have three or more-say, you’re a 60-year-old white man, overweight, with 10 years of daily heartburn, and you used to smoke-you’re in a high-risk group. The American College of Gastroenterology says people like this should be screened with an endoscopy. Yet, only 13% of people who fit this profile actually get tested.

The Red Flags You Can’t Ignore

Most people with early esophageal cancer have no symptoms. That’s why it’s so deadly. By the time they feel something, it’s often advanced. But there are signs that shouldn’t be shrugged off. If you’ve had GERD for years and now notice any of these, see a doctor now:

- Dysphagia: Trouble swallowing, especially solid foods like meat or bread. It starts as a feeling that food gets stuck, then progresses to liquids.

- Unexplained weight loss: Losing 10 pounds or more in six months without trying. No diet, no exercise-just weight falling off.

- Persistent heartburn: Not occasional. Not after spicy food. Heartburn happening more than twice a week for five years or more.

- Food impaction: Food literally gets stuck in your chest or throat. You may need to drink water or even induce vomiting to clear it.

- Chronic hoarseness or cough: A voice that’s been raspy for over two weeks, or a cough that won’t go away, especially at night.

These aren’t "maybe" signs. They’re clinical indicators. Eighty percent of people diagnosed with esophageal cancer had dysphagia. Sixty to seventy percent had unexplained weight loss. And 90% had long-standing GERD. If you have two or more of these, especially with your risk profile, don’t wait for your next checkup. Request an endoscopy.

What Happens During Screening?

Screening for Barrett’s esophagus means an upper endoscopy. It’s not as scary as it sounds. You’re sedated. A thin, flexible tube with a camera goes down your throat. The doctor looks at your esophagus and takes small tissue samples. It takes about 15 minutes. No incisions. No hospital stay.

Modern tools make it even better. Narrow-band imaging and confocal laser endomicroscopy let doctors see cell changes in real time. They can spot early abnormalities that old methods might miss. And now, there’s a new tool called the Cytosponge-a pill you swallow with a string attached. Once it reaches your stomach, it expands into a sponge, collects cells as it’s pulled back up, and those cells are tested for signs of Barrett’s. It’s less invasive, cheaper, and 80% accurate. It’s not everywhere yet, but it’s coming.

The American Gastroenterological Association also has a risk calculator called BE MAPPED. It uses seven factors-your age, sex, BMI, smoking history, GERD duration, family history, and race-to give you a personalized risk score. If your score is high, screening is strongly recommended.

How to Lower Your Risk-For Real

You can’t change your age or your genes. But you can change your habits-and those changes matter.

- Quit smoking: Your risk drops by half within 10 years of quitting. Even if you’ve smoked for decades, it’s never too late.

- Loosen your belt: Losing just 5-10% of your body weight reduces GERD symptoms by 40%. That’s not just about comfort-it’s about preventing cancer.

- Limit alcohol: Heavy drinking increases a different type of esophageal cancer (squamous cell), but even moderate intake adds up. Stick to one drink a day for women, two for men.

- Take your PPIs as prescribed: If you’ve been diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole or esomeprazole can cut your cancer risk by 70%-but only if you take them every day, for years. Skipping doses doesn’t work.

- Get screened: If you’re high risk, don’t wait for symptoms. Endoscopic surveillance every 3-5 years for Barrett’s patients reduces cancer deaths by 60-70%.

And here’s something surprising: people with chronic GERD who get regular medical care actually have a lower risk of other cancers-like colorectal and liver cancer. Why? Because they’re seeing doctors more often. They’re getting screened for other things too. Your GERD might be the ticket to catching something else early.

What’s Next? The Future of Prevention

Researchers are now looking at genetics. Some people have gene variants-like in the CRTC1 gene-that make them 2-3 times more likely to develop Barrett’s from GERD. In the next five years, we may see blood or saliva tests that identify these high-risk individuals before they even have symptoms.

Right now, the best tool we have is awareness. The rise in esophageal adenocarcinoma over the past 50 years tracks almost perfectly with the rise in obesity. In 1976, 15% of Americans were obese. Today, it’s 42%. That’s not a coincidence. We’re eating more, moving less, and our bodies are paying the price.

But we can turn it around. If you have long-term GERD, know your risk. If you’re over 50, male, overweight, or a smoker-get checked. Don’t wait for trouble to show up. Early detection isn’t just helpful. It’s the difference between a 21% survival rate and a 60% one.

Can GERD cause esophageal cancer even if I take medication?

Yes, but not as likely. Taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) daily for five or more years reduces cancer risk by 70% in people with Barrett’s esophagus. But medication doesn’t reverse the cellular changes already made. It only slows further damage. That’s why screening is still necessary-even if your heartburn feels under control.

Is esophageal cancer curable if caught early?

Yes. When caught at an early, localized stage, the five-year survival rate jumps to 50-60%. That’s more than double the overall survival rate of 21%. Most cases are found late because symptoms are ignored. Early detection through endoscopy can catch precancerous changes before they turn into cancer.

Do I need an endoscopy if I have GERD but no symptoms?

It depends on your risk profile. If you’re a man over 50 with chronic GERD (5+ years) and two or more other risk factors-like obesity, smoking, or family history-then yes. Guidelines recommend screening even if you feel fine. Many people with Barrett’s esophagus have no symptoms at all. The damage is silent.

Can weight loss reverse Barrett’s esophagus?

Weight loss doesn’t reverse Barrett’s, but it dramatically reduces acid reflux and slows progression. Losing 5-10% of body weight cuts GERD symptoms by 40%. That means less acid hitting the esophagus, which lowers the chance of further cell changes. It’s not a cure, but it’s one of the most effective ways to protect yourself.

How often should I get screened if I have Barrett’s esophagus?

If you have Barrett’s without dysplasia (abnormal cells), screening every 3-5 years is standard. If low-grade dysplasia is found, you’ll need an endoscopy every 6-12 months. High-grade dysplasia often leads to treatment to remove the abnormal tissue. Never skip follow-ups-this is where early intervention saves lives.

Is there a blood test for esophageal cancer risk?

Not yet for routine use. Right now, endoscopy and cell sampling (like the Cytosponge) are the only reliable methods. But research is advancing fast. Genetic tests for variants like CRTC1 are being studied to identify high-risk individuals before Barrett’s develops. In the next few years, a simple blood or saliva test could become part of standard risk assessment.

What to Do Next

If you’ve had heartburn for five years or more, especially with any of the risk factors listed above, don’t wait. Talk to your doctor about an endoscopy. If you’re not sure whether you qualify, ask about the BE MAPPED risk calculator-it’s free, quick, and accurate. If you smoke, quit. If you’re overweight, start losing weight. If you’re on PPIs, take them consistently. These aren’t just lifestyle tweaks. They’re survival strategies.

Esophageal cancer is rare-but it’s deadly. And it doesn’t come out of nowhere. It grows slowly, silently, over years. You have the power to interrupt that process. Knowledge is your first defense. Action is your second. Don’t let silence be your downfall.

Nupur Vimal

I had GERD for 8 years and never thought twice about it until my cousin died of esophageal cancer at 52. Now I get endoscopies every 3 years. Don't wait for symptoms. The silence kills.

Also stop lying to yourself about 'just a little heartburn' - if it's daily, it's not just indigestion.

RONALD Randolph

This article is accurate, but incomplete. The CDC and ACG guidelines explicitly state that white males over 50 with BMI >30 and >5 years of GERD are Class I candidates for endoscopy. Yet, in my practice, 87% of patients in this category refuse screening because they 'don't feel sick.' This is why American healthcare is failing: denial is not a treatment plan.

John Brown

I'm 58, overweight, former smoker, and had GERD since 35. I got my first endoscopy last year. Found Barrett’s. No dysplasia. Took PPIs daily. Lost 18 lbs. My heartburn is gone. I’m not scared anymore-I’m empowered.

Don’t wait until you’re choking on food. Do the thing. Your future self will thank you.

Christina Bischof

I used to think heartburn was just part of being a mom who eats on the go. Then my dad passed. I didn’t know until it was too late. Now I tell every woman I know over 45: get checked. Even if you feel fine. Even if you think it’s not you. It could be.

Jocelyn Lachapelle

I’m so glad this got shared. My sister ignored her reflux for 12 years. She lost 30 lbs without trying. Then she couldn’t swallow water. They found stage 3 cancer. She’s in remission now, but it took 6 months of chemo. Please, if you’re reading this and have GERD-don’t be like her. Get tested.

Mike Nordby

The BE MAPPED calculator is underutilized. It is validated in multiple prospective cohorts and demonstrates a C-statistic of 0.83 for predicting Barrett’s esophagus. Clinicians should integrate it into routine primary care workflows for patients with chronic GERD. The cost-benefit ratio is overwhelmingly favorable.

John Samuel

Let’s be crystal clear: this isn’t just about acid. It’s about the slow, silent erosion of your dignity, your breath, your future. Every swallow that feels ‘off,’ every night cough, every unexplained weight loss-it’s your body screaming in Morse code. Stop ignoring the dots and dashes.

Get. Screened. Now.

Sai Nguyen

Americans think they’re special. In India, we don’t wait for doctors. We drink ginger tea, avoid fried food, and sleep on our left side. No endoscopy needed. This overmedicalization is a scam.

Michelle M

It’s funny how we treat our bodies like they’re disposable. We ignore the warning lights because we’re busy, tired, or afraid. But the body doesn’t care about your schedule. It just keeps working… until it doesn’t. Maybe this isn’t about cancer. Maybe it’s about learning to listen.

Lisa Davies

I just told my dad to get an endoscopy. He said 'I’m fine.' I sent him this article. He’s scheduling it tomorrow. 🙏❤️ You’re not alone. We’re all scared. But action > fear.

Cassie Henriques

The Cytosponge data is promising, but sensitivity for low-grade dysplasia is still suboptimal (~72%). We need more RCTs comparing it to standard endoscopy in real-world primary care settings. Also, the cost per diagnosis needs to be modeled against long-term oncology burden. Not a silver bullet yet.

Jake Sinatra

I’m a primary care physician. I’ve seen too many patients with stage IV esophageal cancer who had GERD for a decade. I now have a protocol: if a patient over 50 has chronic GERD + any two risk factors, I order BE MAPPED and refer for endoscopy within 30 days. No exceptions. Prevention is not optional.