Patent Expiration: What Happens When Drug Monopolies End

When a patent expiration, the legal end of a drug company’s exclusive right to sell a medication. Also known as drug patent cliff, it’s when a brand-name drug loses its market monopoly and cheaper versions can legally enter the market. This isn’t just a legal detail—it’s the moment millions of people suddenly pay less for their prescriptions. But here’s the catch: just because a generic becomes available doesn’t mean it’s always the right move for everyone.

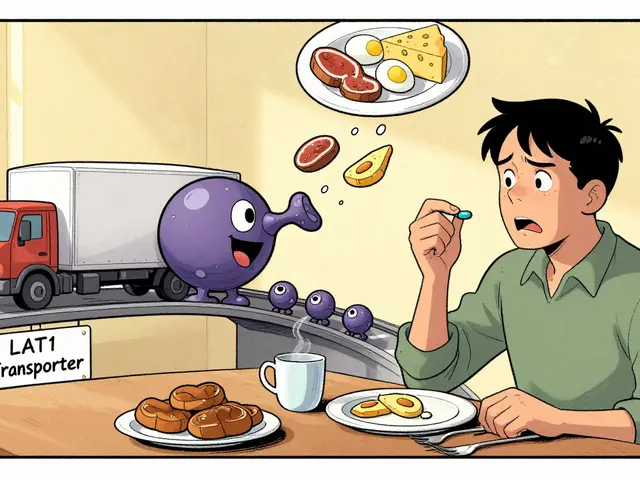

Generic drugs, chemically identical versions of brand-name medications approved by the FDA after patent expiration. They’re not knockoffs—they’re required to work the same way, in the same dose, and with the same safety profile. But the real-world story isn’t always clean. Some kids with epilepsy, older adults on blood thinners, or people with chronic autoimmune conditions report differences when switching. Why? Because fillers, coatings, or absorption rates can vary slightly. That tiny difference can matter when you’re on a tight therapeutic window.

Drug pricing, the cost of medications shaped by patent protections, manufacturing, and market competition. Before patent expiration, a drug like Lipitor or Humira might cost hundreds per month. After? Often under $10. That’s why pharmacies, insurers, and even government programs push generics. But not every patient gets the same access. Some doctors still default to brand names out of habit. Others worry about insurance formularies or patient confusion. And in some cases, the generic version isn’t even available yet—because manufacturing is complex, or the patent was extended through legal loopholes.

Brand name drugs, medications sold under a company’s trademark while under patent protection. These are the ones you see on TV ads, with fancy packaging and big price tags. They’re often the first to market, backed by years of clinical trials. But once patent expiration hits, their sales drop fast—sometimes by 80% or more. That’s why drug companies try to delay it: through new formulations, combination pills, or legal challenges. It’s not always about innovation—it’s about profit.

And then there’s the hidden layer: pharmaceutical patents, legal protections that give companies exclusive rights to sell a drug for up to 20 years from filing. But here’s what most people don’t realize: the clock starts ticking when the patent is filed, not when the drug hits shelves. That means a drug might only have 7–12 years of real market exclusivity after FDA approval. The rest? Years spent in testing, trials, and bureaucracy. Meanwhile, companies file dozens of secondary patents—on coatings, dosing schedules, or delivery methods—to keep generics out longer. This is called evergreening. It’s legal. It’s common. And it keeps prices high.

So when you see a generic version of your medication appear on the shelf, it’s not just a price drop—it’s a system shift. Your doctor might not tell you about it. Your pharmacist might switch you without asking. And if you’re on something like a biologic for rheumatoid arthritis or a complex antidepressant, that switch could mean more than just saving money—it could mean a change in how you feel.

Below, you’ll find real stories from people who’ve been through these switches: parents worried about their kids on asthma meds, seniors catching dangerous interactions after a pharmacy change, and patients wondering why their statin suddenly gave them muscle pain. These aren’t theoretical debates. They’re daily decisions. And understanding patent expiration helps you ask the right questions before your next refill.